Despite not making a third try for the White House this year, Joe Biden might not be done quite yet with holding office--which is often par for the course with vice presidents who don’t end up holding the top job.

Politico reported at the end of last week that Hillary Clinton is considering having Biden, now 74, as her secretary of State, provided, of course, she wins the presidential election next week. Biden has downplayed the possibility of serving in the Cabinet.

Even though they often differed on foreign affairs during President Barack Obama’s term, the idea does make some sense. Biden has always had a passion for international policy and led the Senate Foreign Services Committee. The vice president generally polls far more favorably than Clinton does, no small consideration in the final days of a presidential election. Clinton can also continue to claim the Obama legacy by having Biden in her Cabinet.

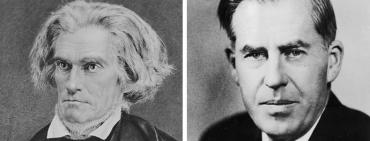

Biden wouldn’t be the first former vice president to hold a Cabinet post which is technically, a lesser office. After serving as vice president under both John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson and spending time in the Senate, John C. Calhoun served as John Tyler’s secretary of State in the last year of his tumultuous presidency. With the Texas annexation front and center, nobody saw Calhoun’s tenure at the State Department as a demotion, especially as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams and Martin Van Buren all used it as a launching pad for the presidency.

If Calhoun’s year in the Tyler Cabinet wasn’t seen as a demotion, the same couldn’t be said of Henry Wallace’s place under Harry Truman. After two terms as Agriculture secretary, Wallace was FDR’s running mate in 1940. Four years later, with concerns about FDR’s health growing, party regulars demanded Wallace’s scalp and the president replaced him with Harry Truman. Early in his fourth term, FDR nominated Wallace to head up the Commerce Department, leading to a tie vote which Truman broke. After Roosevelt died, Truman and Wallace clashed over foreign policy, namely over getting tougher with the Soviet Union. Truman fired Wallace in 1946 and they clashed two years later. Wallace flopped badly as a third party candidate in the 1948 presidential election while Truman went on to a term in his own right.

One other vice president served in a presidential Cabinet--but not for a U.S. president. John C. Breckinridge was a rising political star when he was tapped as James Buchanan’s running mate. As the Democrats split in 1860, with the northern branch of the party supporting Stephen Douglas for president, the southern wing turned to Breckinridge. While Breckinridge lost to Abraham Lincoln, he was elected to the Senate from Kentucky. Breckinridge was a critic of the Lincoln administration’s early efforts in the Civil War and was expelled a few months after taking his Senate seat in 1861. He ended up as a Confederate general and as Jefferson Davis’ last secretary of War during the final months of the war.

Other former vice presidents who never quite made it to the White House also staged political comebacks. George M. Dallas, the Pennsylvania Democrat who was James K. Polk’s understudy, served as ambassador to England under Franklin Pierce and old rival Buchanan. After four years under Lincoln, Hannibal Hamlin served in the Senate and as ambassador to Spain. Levi Morton, who served as Benjamin Harrison’s vice president, was elected governor of New York. Like Dallas, Charles Dawes, who was Calvin Coolidge’s vice president, served as ambassador to England and later led the Reconstruction Finance Corporation as Herbert Hoover attempted to deal with the Great Depression.

Of course, the vice presidency was not highly thought of throughout the nineteenth century and the start of the twentieth century. Most of the former vice presidents who went on to hold other offices did not consider their new positions a step down. The one exception might be Richard M. Johnson. In 1841, a year after getting thrown out of office as Van Buren sought another term, Johnson went on to win a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives. Johnson spent the 1840s trying to win higher office, including an underwhelming bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1844 and a failed gubernatorial campaign. Johnson went back to the Kentucky House and held a seat in it when he died in 1850.